Shouldering - The Workload for Baseball

March 15, 2018

As some of you might know, not too long ago, I wrote an article for Simplifaster.com titled “Myths and Misconceptions of Training the Overhead Athlete”. I’d seen so much stuff online about how to train pitchers that I knee-jerked into writing an article…with one exception. It wasn’t going to be a “This is what I did” piece and expect that to satisfy the audience. With all the crap flying around, I wanted to put to rest the science and application that has been mishandled, miscommunicated, misunderstood and plain dismissed. Parts of that article will be interspersed throughout this piece because I think it’s important to get the science behind the action.

Unless you are in the game on a day-to-day basis, it’s impossible to comprehend what it’s like to train a baseball player let alone a pitcher. This is not to say that those operating and coaching at a training facility aren’t knowledgeable. I like some of the information coming out in those areas. What I am saying, is that I know those programs would look a bit different if these personal coaches had a bullpen and five starters they needed to individualize programs for. They would be better programs because of the spontaneous adjustments that need to be made. Therefore, I thought it important for me, a +35-year S&C veteran and 12-yar major league strength and conditioning coach to give my experience; not my opinion.

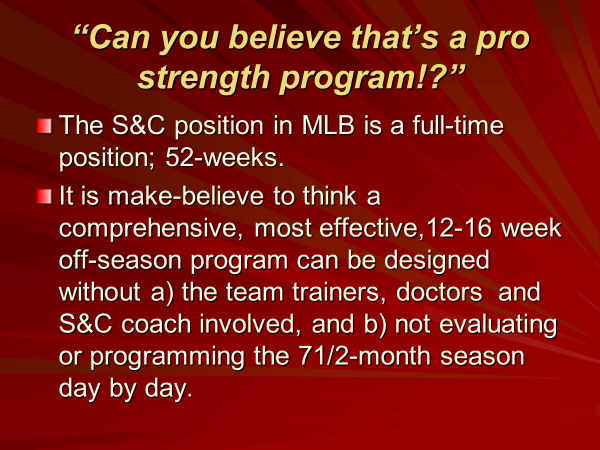

A slide from my presentation at the 2009 NSCA Sport Specific Training Conference.

A Couple of Quick Thoughts

- It’s absurd to think that a healthy shoulder is maintained by light-load resistance training, band exercises and 3lb rotator cuff exercises alone! Those with common sense and knowledge of the game of baseball know that. Baseball in general has long subscribed to lifting light weights to get strong- nonsensical.

- Easy to forget- The scapula is one-half of the glenohumeral joint (glenoid cavity) and could be considered the greatest pivotal avenue for shoulder health for one reason: If the head of the humerus essentially stays centered in the glenoid (the scapula “stays”; strength-based) during the entire phase of throwing then you are golden! Just so happens that the typical and likely most effective ways to strengthen scapular movement and stability is through “pulling” exercises.

- Push-pull balancing remains a relevant training approach. Insensitivity to this philosophy is a risky proposition. We all know that push-pull balance means not only the amount of pulling exercises versus pushing exercises but also the balancing and contribution of the accelerators, decelerators and stabilizers to shoulder health. Work in this area- as does the science, intuition and common sense- clearly illustrates balance is necessary for performance and health. It’s implied or suggested all through the peer reviewed literature.

- Of the dozens of abstracts and studies I’ve read addressing the topic of concentric to eccentric ratios, nearly all of them state that the ratio was low due to the low eccentric strength in the dominant arm.

I’ve said this before, nowhere have I found any documentation that overhead lifting is detrimental to the throwing or overhead athlete shoulder. Now, that doesn’t mean that you must overhead lift. It does mean that if you think that a well-designed program should have overhead lifting then power to you!

- The wise practitioner will look outside of the throwing shoulder studies and look at overhead athletes in general if they are looking for a knowledge base wide enough- scientifically and as a practical matter- to come up with a solution or at least some damn good hypotheses on shoulder health. Can’t tell you how many times I have drawn on my work with tennis, swimming and volleyball athletes.

First things first!

Every conversation that includes pitching, velocity and arm health has to be underpinned with only one consistent thought and caveat: Arm health and velocity for a pitcher is never any one or two muscles or any one method. No one part of the body throws the baseball. In fact, it is thrown with the ENTIRE body. It’s laughable to talk about arm health- or rehabilitation- without mentioning other regions of the body in terms of strength, flexibility, stability, etc. Yet we see it all the time. Coaches, ATC’s and doctors talking about what needs to be done with the shoulder, how much rest is needed, recovery techniques. Never, What is the frequency of the training bouts, What is the intensity of the training, How strong is the athlete, What exercises has this athlete been exposed to, What lower body power and strength measures do we have. Not only that, but the monitoring of each and every throw is important from warm up to warm down (volume). However, intensity is important as well but we don’t see a radar gun in the bullpen for a starting pitcher’s side or the warm up throws in the outfield before the mound- how hard you throw matters, just as much as how fast you run or how much weight you lift; all intensity based. So, there is plenty of holes in the current investigations of arm health that aren’t being filled. For sure, the easiest to attack is the integrity of the entire kinetic chain.

“The significant amount of muscle activity (assessed by maximal voluntary isometric contraction) elicited by the biceps femoris (125%) and gluteus maximus (170%) of the stride leg, eccentrically controls hip flexion deceleration and deceleration of the throwing arm that accompanies the follow-through portion of the pitch (Campbell, et. al.,2010).”

This is one of many examples in the research that let’s us know that it is the whole body doing the work and the importance of the lower body that we always talk about, but rarely do we hear a coach expound on the kinetics. This information also implies that if a strength program for a pitcher does not include pulling from the ground or one and two-legged RDL’s (I would do both), expect less than the best results in shoulder health and performance.

David Stodden, Phd, CSCS, who is currently the Professor & Interim Director, Yvonne & Schuyler Moore Child Development Research Center, has spent some time at the American Sports Medicine Institute (teamed with Glenn Fleisig of ASMI on a few research projects). He and others, (Stodden et. al., 2005) summarized their study, “Relationship of Biomechanical Factors to Baseball Pitching Velocity: Within Pitcher Variation”, as such: …the effects of increased pelvis and upper torso rotational velocities (Stodden et al., 2001), trunk tilt forward at ball release, increased shoulder and elbow proximal force, increased elbow flexion torque, decreased horizontal adduction at foot contact, and changes in relative temporal parameters suggest that when a pitcher increased ball velocity, it was due to a more effective transfer of momentum in the kinetic chain. “Lower Extremity Muscle Activation During Baseball Pitching” by Campbell, et. al. 2010, states what we know is the obvious in the lower extremity during the pitching motion but rarely hear a strength and conditioning coach mention in these terms: Rotating the trunk and upper extremity requires a stable base of support upon which to rotate and, thus, simultaneous and substantial muscle activity from the stride leg and trial leg. This brief bilateral base of support serves to promote the optimal transfer of momentum generated from the initial phases of the pitch. Furthermore, during the latter part of phase 3 (stride foot contact to ball release) and throughout phase 4 (ball release to 0.5 seconds after ball release), the stride leg musculature must eccentrically and dynamically control the ankle, knee, and hip joints as the trunk and upper extremities are decelerating. Two good pieces of documentation, and believe me there’s plenty more, that should be clear to anyone working with the overhead athlete, that it is a “kinetic chain reaction” that throws the ball and therefore implies that the entire chain needs to be assessed if one is looking at arm issues (strength, pain, injury, velocity).

When talking about arm health, it is our responsibility to add the that several areas of the musculature needs to be examined for strengths, weaknesses, imbalances, etc., and not just the arm.

The Scapula is a great place to start enforcing shoulder health and performance

As are the words balance, imbalance and ratio, the scapula is mentioned in the majority of research on clean shoulder function of the overhead athlete. I really think that is lost on most coaches and if I catch myself, I find I focus on the shoulder and pulling strengths and lose sight of the intent of shoulder function- stabilize the scapula during throwing/overhead movements. In my conversations with them, Mike Reinold (PT, DPT, SCS, CSCS, Champion Physical Therapy and Performance, formerly of the Red Sox) and Rob Panariello (PT, ATC, CSCS, founding partner and Chief Clinical Officer of Professional Physical Therapy), both were clear on the importance of scapular stability and strength. In fact, very little of the discussion was about the rotator cuff or elbow.

Panariello feels that building a base of stability in the shoulder comes from strength. That the head of the humerus stays in the glenoid because of strength. My personal philosophy is that strength is the basis for all performance. So, he had me convinced when he implied that an early, solid strength program covers it all; no real need then for a more complex approach. But what he said next was as important. He followed by telling me that training the humerus to quickly center is an important piece as well, specifically after injury- training that involved high accels/decels, tempo and perturbation of the shoulder were necessary for that adaptation. As in training, a foundation has to be established before specialization occurs and without strength, special exercises will not provide optimal strength and stability.

Let’s take a look at what makes the scapula move…or not. The primary muscles that control scapular movements are the scapulothoracic muscles- the trapezius, serratus anterior, levator scapulae, rhomboids, and pectoralis minor (Reinhold, M. et.al., 2009). However, most often mentioned in my review of the literature for maintaining balance and health are the trapezius, serratus anterior and rhomboids, as in Rasouli, A. et. al., 2017. As the majority of the studies on the topic indicated and many believe, weakness, fatigue, injury or as Reinhold calls it, when “normal patterns are disrupted”, leads to shoulder (glenohumeral) injury. It’s clear to me that for the shoulder alone, the scapula is the focal point of health. If the scapula can move or resist poor movement through strength and stability then the cuff stands a better chance of being pain free. While the rotator cuff is a point of interest and sometimes the focus, I say that scapular movement and stability through strength will cure a lot of shoulder ills and maybe a few Tommy John’s.

One last note on the scapula- the deadlift!! It is by far the most underrated scapular retracting exercise for strength and rehabilitation after injury. Not only is it great for lower body strength but pulling from the ground with the scapulas pinched to together is a challenge that the scapula must overcome, particularly and intentionally with heavy weight. As I’ve said many times before, steering clear of heavy weight (90-100% intensity) is a mistake for any sport and has been an unjustified stigma in baseball since weight training’s inception into the game. So, we’re clear, heavy weights come after technique is competent and strength is acquired after a background of repetition volume. The fear of heavy deadlifting in baseball should only come from two things: the athlete is not prepared for it or the coach can’t teach and program it.

The following is my recommendation for shoulder and arm health based on the literature and my experiences:

Balance pushing and pulling

The balance and ratio of antagonists and agonists or eccentric and concentric strength in throwing kinetics is stated in nearly every like study or article I looked at. Imbalance is looked upon always as an injury culprit. The structure is already out of balance- the dominant shoulder is doing many times the amount of work going anterior than posterior. Consequently, because backside musculature is at a deficit to begin with, and that nowhere has it been documented anecdotally or in the science where the scapulothoracic muscles overpower the throwing motion causing shoulder abnormalities or injury, then sensitivity to push/pull balance is critical by deduction. In fact, you could suggest that if the scapula is in good shape, the cuff and the elbow will be of little worry. The question is what ratio are we looking at? I recommend a 1:2 push to pull ratio. Honestly, I usually programmed a 2:3 or 3:4 depending on body type and medical history. Typically, it was unnecessary to stray from that template based on a performance and health standpoint. That method will cover the overwhelming majority of overhead athletes. That being said, now that I’ve done this science-finding mission, I’ve changed my mind. Merely because I see the research leaning heavily on scapulothoracic musculature and the amount of evidence from other overhead studies of overworked sporting movements.

While the rotator cuff is talked about in terms of external and internal rotation, and ratios and imbalance, the discussion on scapular placement and movement during throwing is a way more focused and detailed commentary within the literature. When I read several comments similar to the one in Oliver, G. et. al. (2016), “In throwing athletes, proper pelvis and scapular positioning are vital to the overall function of the shoulder as kinetic energy is transferred from the lower extremity through the pelvis, trunk, and scapula onto the shoulder (Kibler WB, et. al., 2013).”, everything becomes clearer to me. Despite any success I had training the “game’s” finest pitchers, perhaps I had undertrained the pulling portion of the programs; the musculature most involved in deceleration and scapula strength and stability could have been better in my new estimation!

How do you do 1:2 ratio? Easy. Do the math. Add up the sets and reps, right? Well, not really. You see, not all pushes and pulls are analogous. A chest press is not the equivalent press to an overhead latissimus pulldown; it doesn’t cover the same angles, region or range of motion. Which is why I created the training method “Reciprocal Training”. Same plane, same grip. The thumbs-facing-in grip of the flat bench press corresponds to a seated row with the same grip and same plane; a thumbs-up dumbbell front raise corresponds to a thumbs-up straight arm pullover or pulldown; and a reverse barbell curl (palms facing down grip) pairs up with a same-grip tricep cable pushdown. You get the point. Then it is a matter of sets and reps. In this case, balance would be the same intensity as well. In other words, when in a strength cycle (sets of 5 repetitions), the paired exercises would both be performed for the same repetitions and maximum poundage. Also, if there are three sets of bench presses (working sets) then there are six sets of rows. It sounds like a lot but for me the research intimidates me a little on that side. It certainly should grab your attention.

To date there has been nothing conclusive as to what exact push:pull set/rep/load ratio per workout, meso- or macrocycle is best. Nor, is there any agreement on the perfect strength ratios of the internal and external rotators or concentric internal rotation and eccentric external rotation. Still, coaches have used a few combinations (1:2, 2:3, 3:4).

Wilk, K. E., et. al., 2009 agrees with the thought that “proper balance between agonist and antagonist muscle groups” provides dynamic stability to the shoulder joint. He also states that proper balance of the “glenohumeral joint external rotator muscles should be at least 65% of the strength of the internal rotator muscles (Wilk, K.E. et. al., 1997)”. Other researchers have given their take on internal/external rotator muscle balance but I chose Kevin Wilk (PT, DPT, FAPTA) who has extensively studied this. In the same 2009 study Wilk states, “…the external-internal rotator muscles strength ratio should be 66% to 75% (Wilk, K.E, et. al. 1993; Wilk, K.E., et. al. 1992; Wilk, K.E. et. al., 1997).” Whether these numbers are the case or not is not the point, but provide a stake-in-the-ground reflecting that balance and ratios are in fact important.

Pull in a 180-degree ROM

As Stodden says, “How can we say we need a balanced attack on the shoulder but not pull or press past 90 degrees!?” Answer- WE CAN’T! If I want to stabilize the scap every way possible I want to pull (retract), elevate and upper rotate every possible chance to counteract the powerful forward movement of pitching. That being said, how can we talk about balance and ratios and not pull in a 180-degree range?! A range afforded us. If not, then that practitioner does not subscribe to training in a full range of motion (ROM) which is one of the critical points of training methodology. Curious philosophy when one considers that injury risk is higher when there is weakness at any place during an active range of motion; particularly at an extreme ROM (fully extended or fully flexed).

I recommend one and two arm movements for horizontal and vertical (downwards and upwards) pulling. For example, horizontal rows with emphasis on “pinching” the shoulder blades together at the finish of the pull and definitely reaching out as far as the shoulders can stretch forward (not a toe-touching move; no low back-rounding) before the next pull. Reaching forward is a technique that is avoided by most and it’s a mistake. This reach forward helps to maintain flexibility and strength in a similar position to the follow-through in pitching; the phase most stressful to the arm, the phase where most arm problems show up and a range of motion where the rhomboids can be trained optimally. Vertical upwards pulling (upright rowing) is important as well given the importance of the trapezius in maintaining scapular placement and movement. And, of course vertical downwards pulling (lat pulldown) that completes the pulling range of motion. Technically, vertical downward pulling ranges from 180-91 degrees, vertical upward pulling ranges from “0”- 89 degress and horizontal is at 90 degrees. But we all know development should occur at all angles to be comprehensive. One exception- I do resist the idea of most 2-arm grips narrower than shoulder width. This narrow grip exposes the humerus, specifically the head of the humerus, to a stressful position (concentrically and eccentrically) that is uncommon for most people, especially a pitcher.

Train for great lower body strength

Nothing any beginning strength and conditioning coach does not know- the legs provide the conduit for the display of force by the upper body. And, it’s always good to have good supporting info even if it’s elementary. I’ll start with this: In a meta-analysis (compiling research on a topic and combining the subject population and running statistics on a larger sample size for statistical significance) of ball velocities and overhead athletes, Myers, N.L., et. al., 2015, suggests that “…these athletes use the entire kinetic chain combining multiple anatomical segments and regions to generate force in a proximal to distal fashion.” No coincidence that the programs in the meta that did not find any significant increases in ball velocity, “were relegated to upper body” exercises. Looking at gluteal muscle group activation and throwing motions of softball position players, Oliver, G.D, et. al. (2013), is more than clear that for “…throwing athletes, proper pelvis and scapular positioning are vital to the overall function of the shoulder…” while the energy of the motion is transferred from the lower body “…through the pelvis, trunk, and scapula onto the shoulder.” Oliver, et. al. 2016, is again clear by reiterating- “It is known that pelvic stabilization is needed for essential scapular function...”, going on to cite original research and later to explain that both single and double leg support are important for upper extremity performance. Actually, there are a few other good lumbopelvic studies pointing to increases in shoulder load when there’s a decrease in energy generation from the hip complex (Gilmer, G.G., et. al. 2017). Evidently, and I’m sure there are plenty of other studies pointing to the same conclusion, lower body strength is not only important for delivering the force through “the chain” but is critical for scapular positioning and function.

Now for some plain folk talk. Here it is- if you are an overhead athlete, train your lower body for strength and power so the upper body can perform at the best possible level. Specifically, for pitchers a strong lower body will influence scapula positioning and therefore improve shoulder health and likely decrease stress on the elbow. Make no mistake: If an athlete is of college age or older, 10lb kettlebell RDL’s or 40lb goblet squats won’t cut it. Use heavy weights (+85% intensity) and get strong!

Don’t avoid exercises

“What you resist persists” as my wife likes to say to her clients, and there is a parallel here. Avoidance of exercises for no good reason gets you nothing. Let me first dispel a myth: At the risk of sounding Draconian, there is hardly an exercise that a pitcher/fielder cannot perform under a supervised, well thought out program with an intent towards performance. I don’t know of one documented incident- studied or anecdotally- that has proven an exercise unworthy for a baseball or overhead athlete. In other words, an exercise was performed and over time sports performance decreased, or an exercise was performed and proven the primary cause for injury while throwing. Avoiding exercise because of a stigma and not scientific information, well, you know the typical outcome. No weight training program ever ruined an overhead athletes career. Though, a poorly designed, supervised and implemented program can end one in one day! That being said, given a healthy, functional athlete, if you are avoiding an exercise because you think it will cause injury, it’s possible that you might create one.

And, to coin a term we used in the 7th grade (1970 for me), Duh?!- Of course “well thought out” means a physical assessment of the athlete is performed indicating what methods are appropriate and safe.

Train eccentrically

In the Chris Beardsley paper “Why does eccentric training help prevent muscle strains?”, there is some interesting information about eccentric training. I have to admit, I have done little eccentric strength training in the past for pitchers but that changes today! My pitchers did lift heavy in literally every exercise from bench press, to squat to reverse arm curls, and while I felt they were the strongest in baseball, I can comprehend now that the eccentric strength wasn’t where it should have been for the shoulder complex. In short, regular weight training techniques increases eccentric strength but not the way eccentric training does. To me, performing an exercise slow eccentrically is not eccentric training. That’s accentuating the eccentric. That’s different. And I agree with Panariello, if it’s slow in any direction it better be heavy! If you aren’t strong, how will you be strong at high speeds as in deceleration? If you are trying to counteract the dynamic, high speed force and deceleration of throwing by performing slow eccentrics with light weights (say, <80%), what was your thinking?! Doesn’t make any sense at all. Rehab-ish exercises and loads are not performance training, therefore use weights at 90% or above, low repetition (3-5 reps) for eccentrics. That goes for pulls and presses. Keep remembering, pitching is a dynamic event!

Throwers 10

Kevin Wilk has published and presented on the topic of shoulder health many times over the years. During my review of this topic I ran into this video titled The Throwers Ten Program https://www.kevinwilkblog.com/new-blog-rons-test/. It was developed by him and Dr. James Andrews (American Sports Medicine Institute). The video will speak for itself. Here is the key to what Kevin has offered: its organized and sound and should be included as a regimen for throwers. Now, thit doesn’t mean that intense weight training, balance in the shoulder and conditioning is not as important. It is. However, as the literature says, the rotator cuff work is a bit easier and less complex to attack than the overall musculature in the shoulder. That also means that these tubing exercise will isolate certain parts of cuff that sometimes general strength work might not. For many of us our team’s ATC handle these methods but that doesn’t mean we can’t reinforce it or even better, include some of these exercises as warm ups to weight training.

Summary

- Even though I looked at studies of overhead athletes and not exclusively baseball pitchers/throwers, the story and more importantly the summary of the data, was nearly identical every time- imbalances and poor strength ratios (favoring the agonists) in the musculature of the shoulder leads to pain and injury.

- The entire body contributes to shoulder health and performance in overhead athletes.

- The scapula appears to be the focal point of shoulder health even though the rotator cuff is often targeted. Proper and efficient positioning and movement of the scapula during shoulder movement can decease the chance of rotator cuff pain and injury thereby improving performance. There is also evidence to suggest elbow health is related to scapular activity.

- Push-pull balance in the shoulder is relevant and S&C coaches should be sensitive to the issue for overhead athletes. Based on the evidence and common sense it’s likely that pull volume should be significantly higher than pressing volume (I recommend a 2:1 ratio) for decreasing the risk of poor shoulder function, pain and injury.

- Given a healthy athlete, there are no forbidden exercises for the overhead athlete. Also, there has not been any information that points to limiting range of motion while exercising or weight training.

- Eccentric training, not slow lifting tempo with light weights, would seem to benefit the overhead athlete given the poor ratio of eccentric (deceleration) strength to concentric strength during arm movements.

Beardsley, C. Why does eccentric training help prevent muscle strains? https://www.strengthandconditioningresearch.com/

Campbell, Brian M; Stodden, David F; Nixon, Megan K. Lower Extremity Muscle Activation During Baseball Pitching. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 2010

Kibler WB, Wilkes T, Sciascia A. Mechanics and pathomechanics in the overhead athlete. Clinical Sports Medicine, 2013.

Gilmer GG, Washington JK, Dugas J, Andrews J, Oliver GD. The Role of Lumbopelvic-Hip Complex Stability in Softball Throwing Mechanics. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 2017

Oliver, G. Relationship between gluteal muscle activation and upper extremity kinematics and kinetics in softball position players. Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing, 2013.

Oliver, G.D.; Plummer, H.A.; Gascon, S.S. Electromyographic Analysis of Traditional and Kinetic Chain Exercises for Dynamic Shoulder Movements. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 2016.

Rasouli, A., Jamshidi, A., Sohani, S. Research Paper: Comparing the Isometric Strength of the Shoulder and Scapulothoracic Muscles in Volleyball and Futsal Athletes. Found on Research Gate, 2017.

Stodden, D.F., Fleisig, G.S., McLean, S.P., Lyman, S.L., & Andrews, J.R. Relationship of trunk kinematics to pitched ball velocity. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 2001

Stodden, D.F., Fleisig, G.S., McLean, S.P., Andrews, J.R. Relationship of Biomechanical Factors to Baseball Pitching Velocity: Within Pitcher Variation. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 2005.

Wilk K.E., Arrigo C. An integrated approach to upper extremity exercises. Orthopaedic Physical Therapy Clinics of North America, 1992

Wilk K.E., Andrews J.R., Arrigo C.A., Keirns M.A., Erber D.J. The strength characteristics of internal and external rotator muscles in professional baseball pitchers. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 1993.

Wilk K.E., Arrigo C.A., Andrews J.R. Current concepts: the stabilizing structures of the glenohumeral joint. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 1997.

Wilk K.E., Obma, P., Simpson II, C.D., Cain, E.L., Dugas, J., Andrews, J.R. Shoulder Injuries in the Overhead Athlete. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 2009.

Myers, N.L.; Sciascia, A.D.; Westgate, P.M.; Kibler, W.B.; Uhl, T.L. Increasing Ball Velocity in the Overhead Athlete: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 2015.